Marking 25 Years of the Royal Drawing School

To celebrate the School's 25th anniversary, 25 artists and creatives share with us how drawing informs their practice.

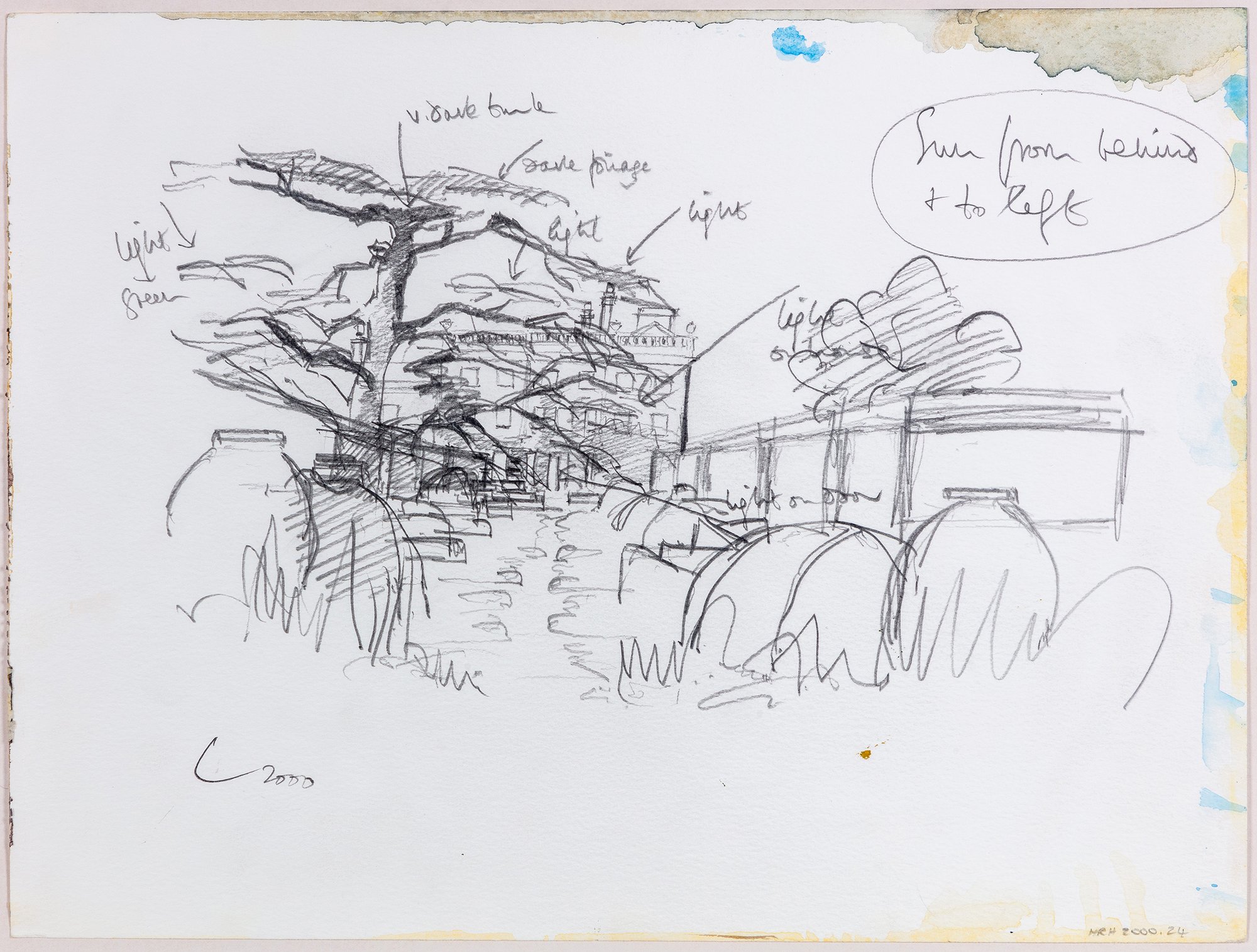

His Majesty King Charles III

Highgrove from the Thyme Walk, 2000. Pencil on paper, 37.5cm x 48cm.

His Majesty King Charles III

Alice Oswald

“I have always loved Paul Klee’s description of drawing as ‘taking a line for a walk’ and for a while I adopted a daily practice of copying his exercises. It was a way of catching the shape and melody of a poem before knowing its language. This image was drawn in oil pastel, with biro notes added at the end. It has the feeling of standing by a river, looking at the other side, which is always brighter and stranger.”

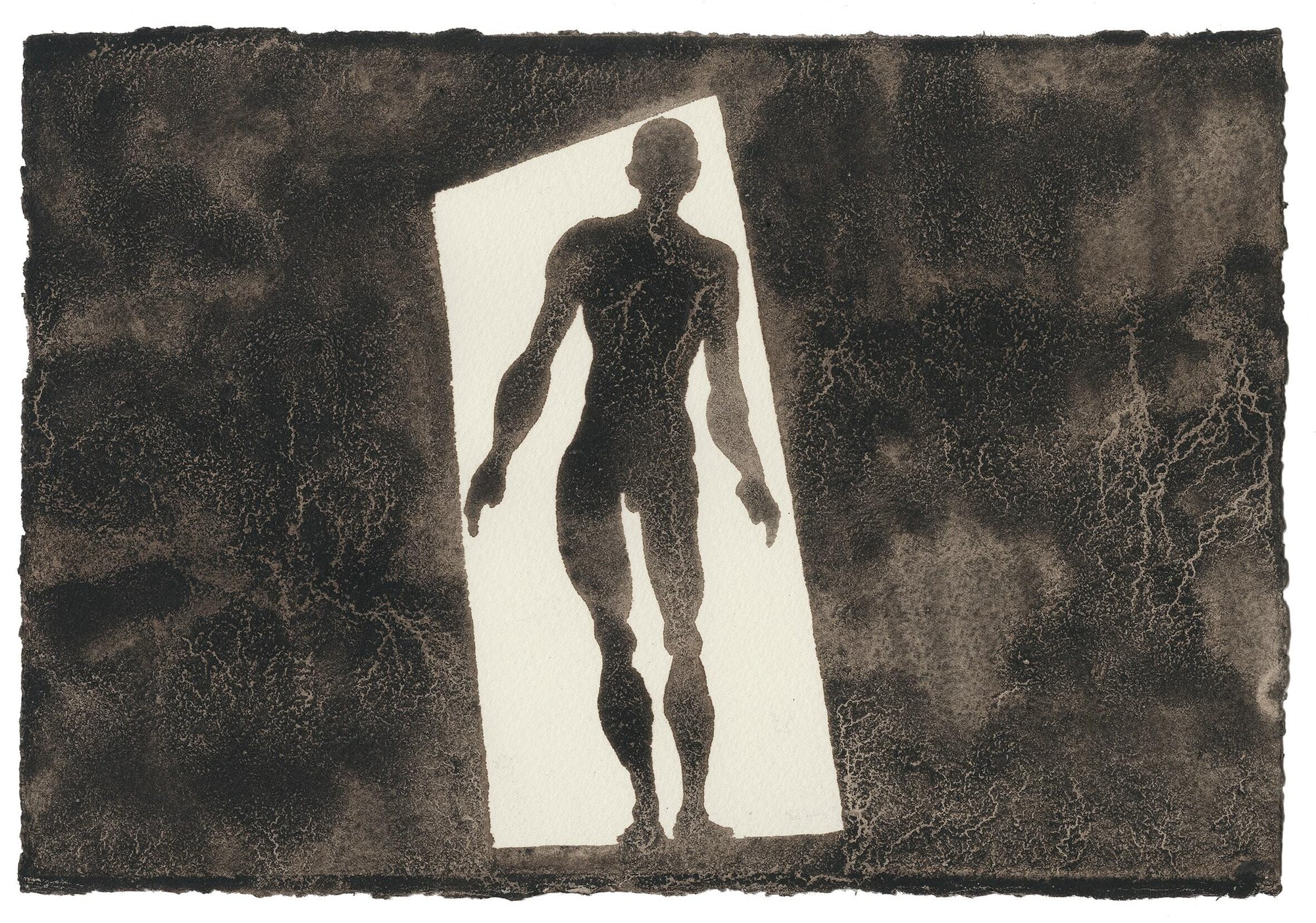

Antony Gormley

“What is drawing? What does it mean to draw?

For me, drawing is a form of thinking that requires tuning in to the behaviour of substances as much as to the behaviour of the unconscious, like reading images in tea leaves, trying to make a map of a path of feeling, a trajectory of thought.

Drawings have immediacy. In a good session, drawing can be like going for a rugged, physical adventure on a blustery day with changing conditions of light and rain. A day passed without drawing is a day lost.”

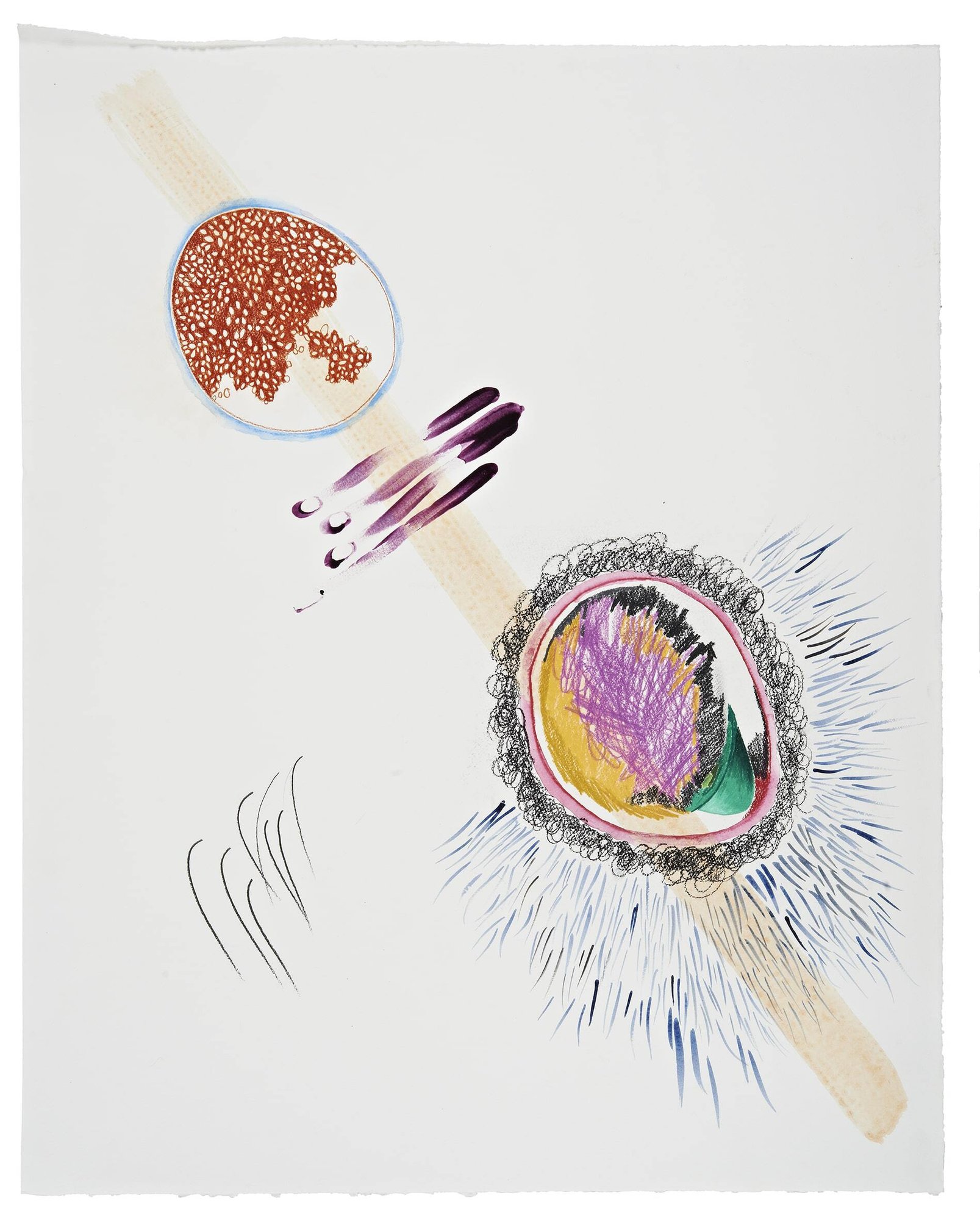

Bharti Kher

“…my drawings pre-empt all of my other works; I don’t really know how or why but they do and there’s a process of trust and intuition which is part of the process of drawing... I’m learning how to go with that, to take a line for a walk, take myself on a journey with the materials—to even be free of myself.”

Catherine Goodman CBE LVO

Founding Artistic Director, RDS

Primordial Landscape, 2024. Charcoal and pastel, 76 x 56.5cm.

Catherine Goodman

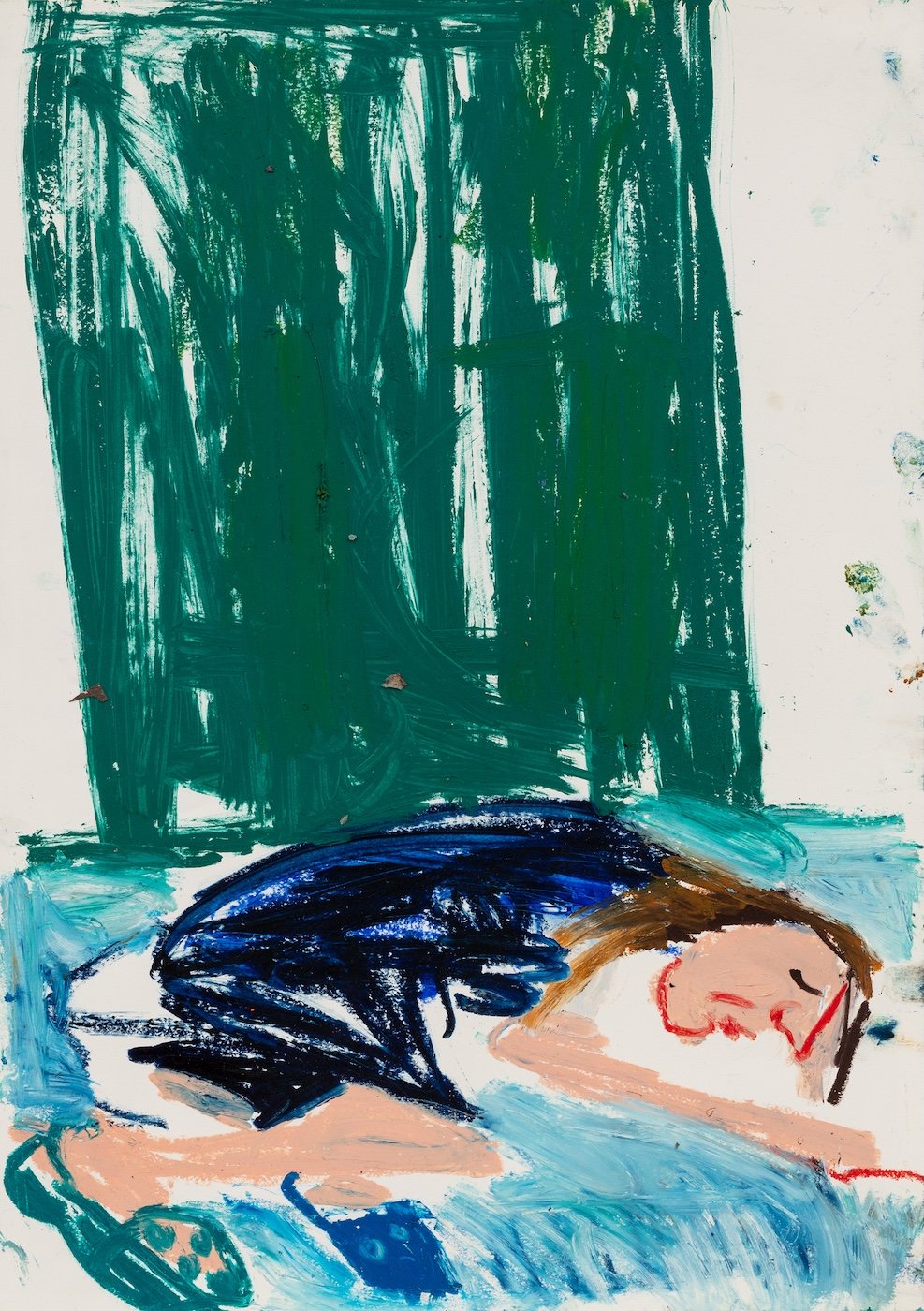

Pictures of What I Did Not See 12, 2019. Pastel and oil stick on paper, 42 x 59.4cm. Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Pictures of What I Did Not See 12, 2019. Pastel and oil stick on paper, 42 x 59.4cm. Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

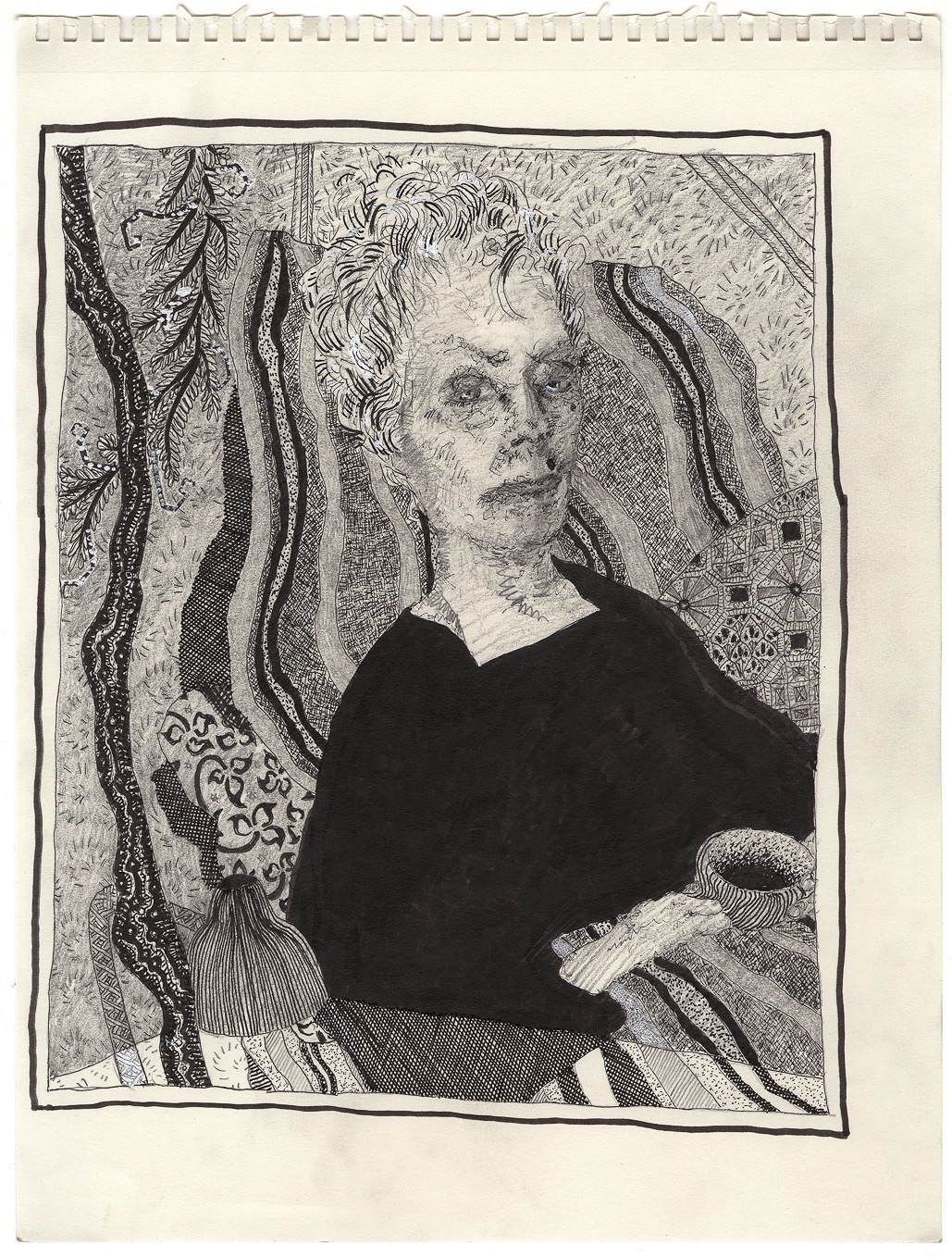

Chantal Joffe

“These drawings are hard to talk about. I made them after I’d been ill and was still recovering—they document what happened and were made in a frenzy. No mark was hard enough or fast enough. I used oil sticks so savagely that they got mashed up in the drawings. I also used pencils, pastels, crayons, and anything else that I had. Making these works made the unbearable bearable to me—I could put it outside myself. By drawing what happened, I could live with it.”

Pictures of What I Did Not See 12, 2019. Pastel and oil stick on paper, 42 x 59.4cm.

Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

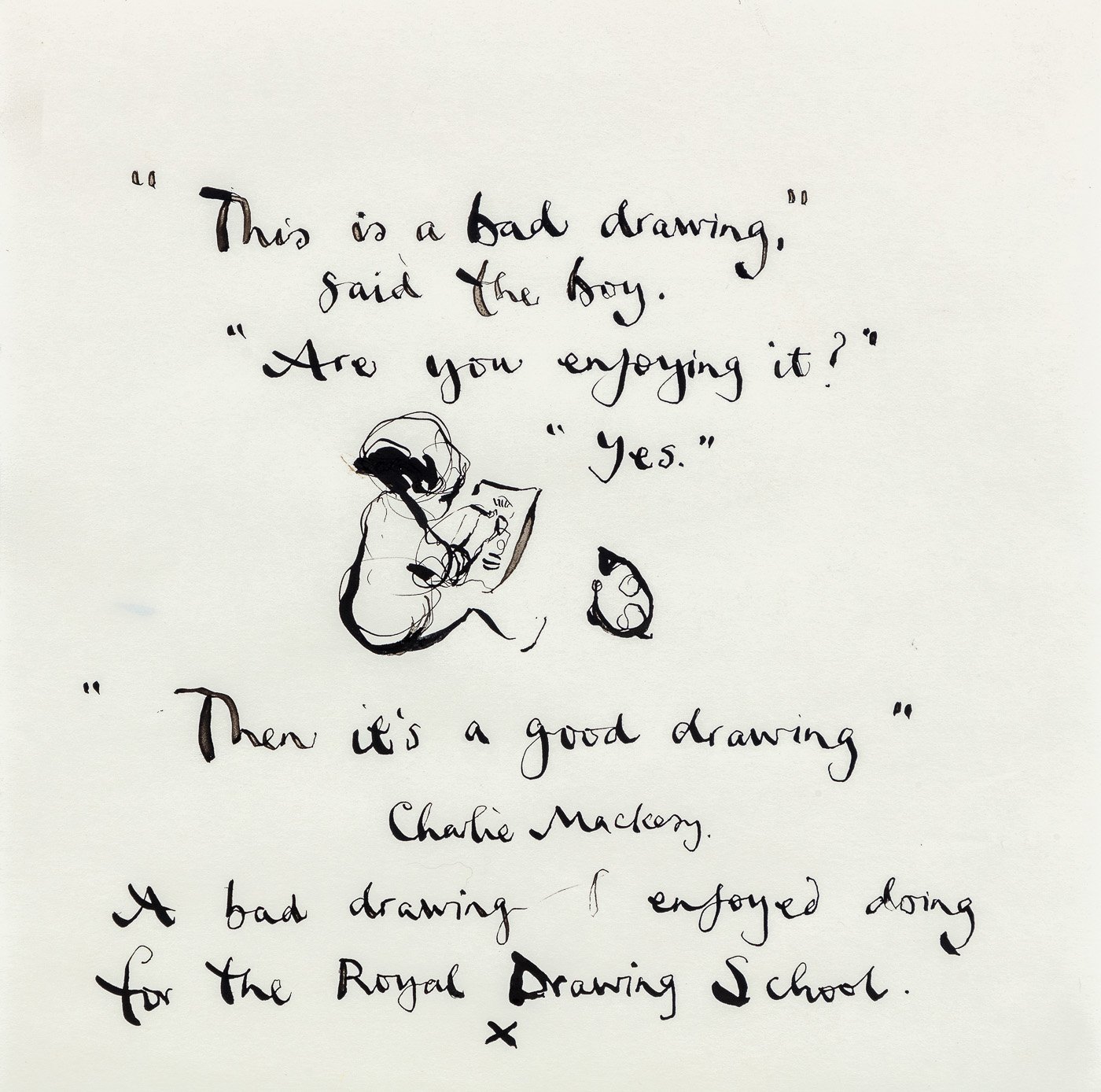

Charlie Mackesy

“One of the best things for me about drawing is how it feels during the making of it—which is often better than the experience of finishing it. I would say that the healing nature of mark making probably saved my life. The experience of it—the sensation of my entire being focused on the movement, the making of lines, marks and shades from the hip—keeping one step ahead of the harsh editor within me—is incredible. It’s like a drug of sorts—a world of endless possibility.”

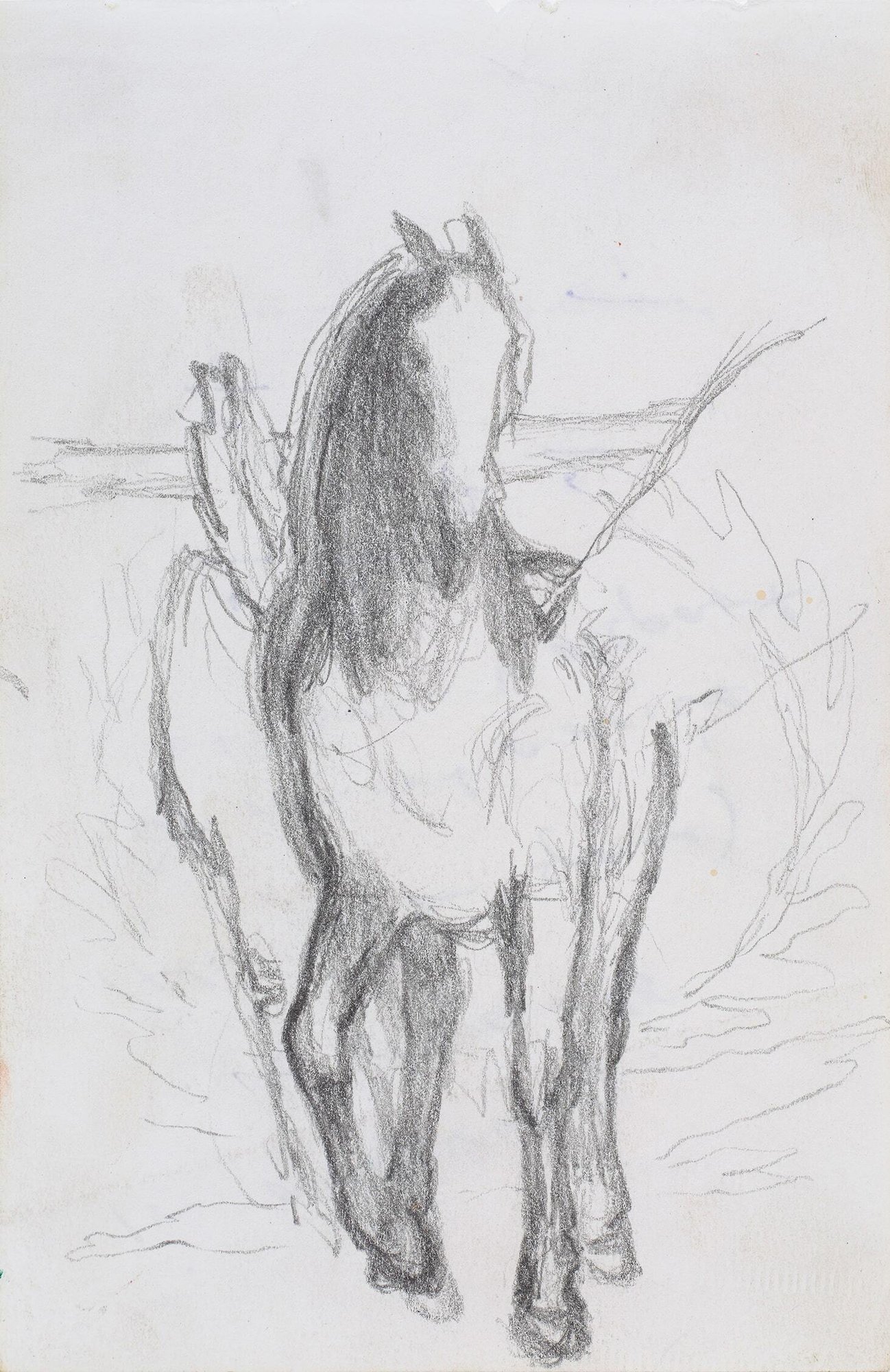

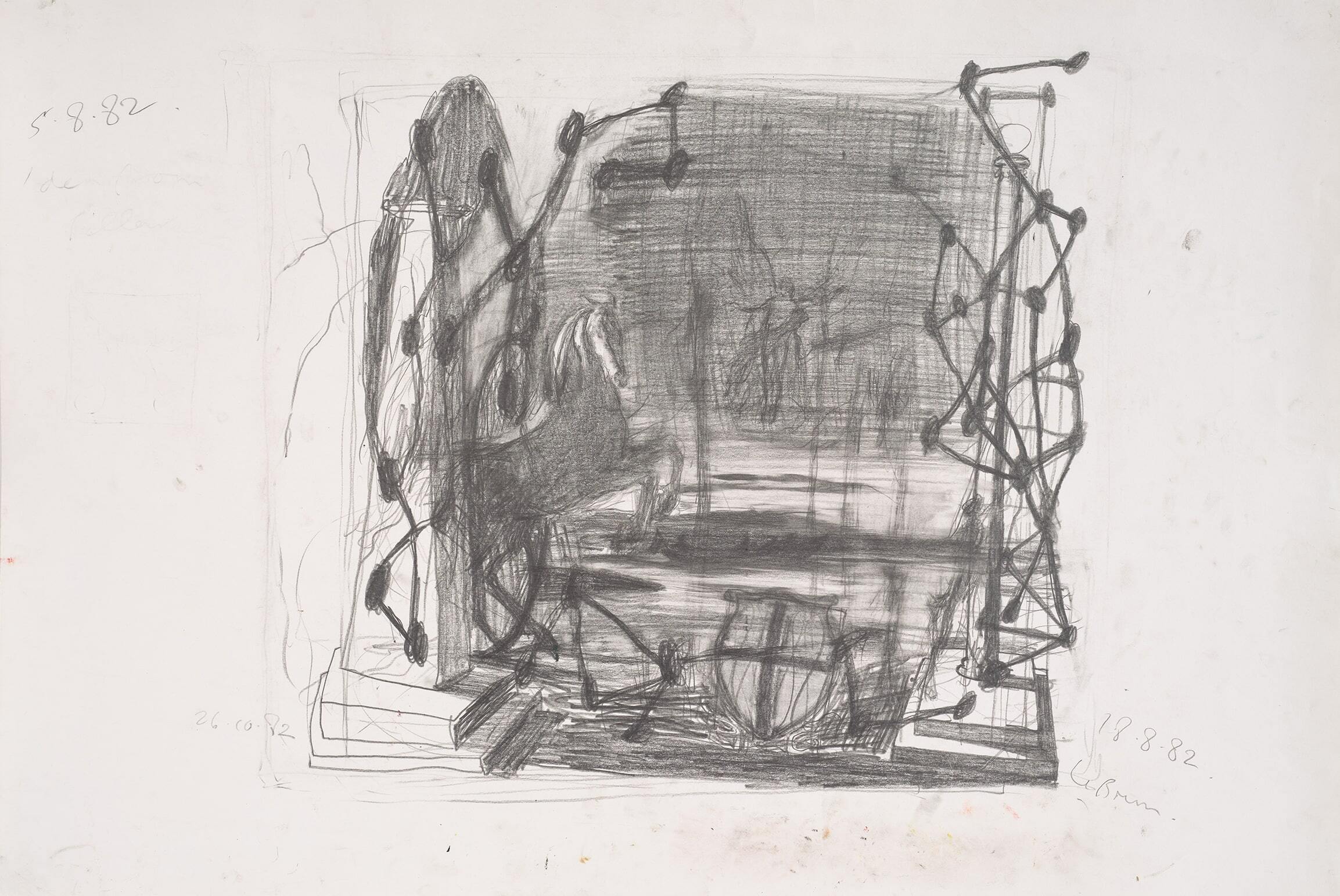

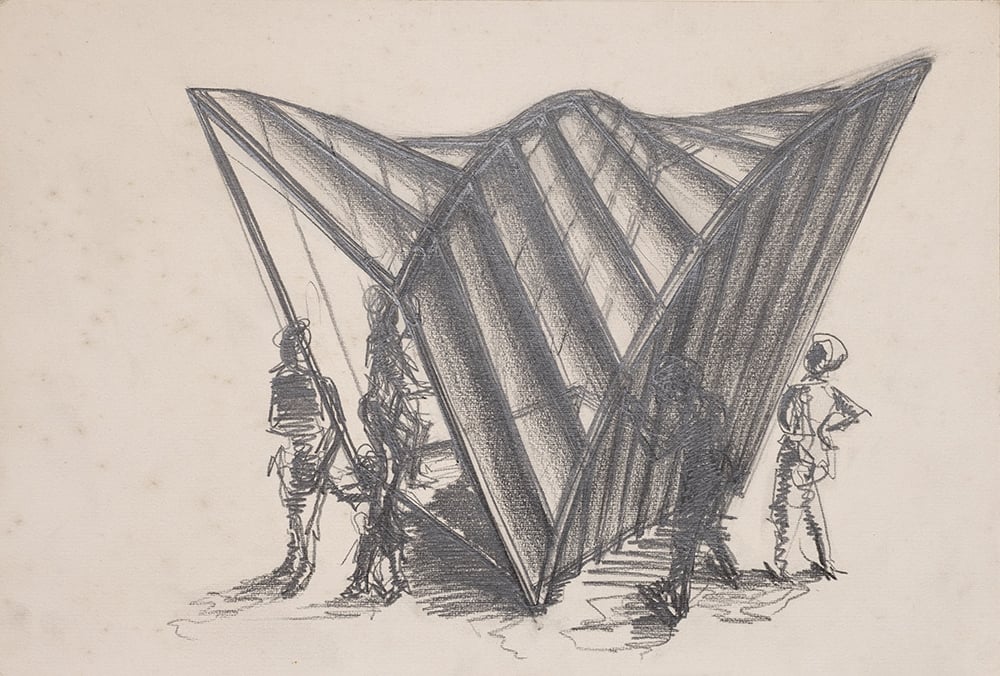

Idea for ‘Pillar’, 1982. Graphite on paper, 68.5 x 101.5cm.

Idea for ‘Pillar’, 1982. Graphite on paper, 68.5 x 101.5cm.Christopher Le Brun

Christopher Le Brun

“Drawings are frequently forerunners, accompanied by a strong sense of “elsewhere”. What is depicted is called to mind, whereas painting and sculpture, being so palpable and physical, have a presence that is reward enough.

I think of drawing as rather a self-effacing medium, as its means are very ordinary. But it nevertheless serves as the deeply valued and everhopeful attendant, forever planning great things in the foothills, en route to painting’s mountain.”

Cornelia Parker

-1.jpg?width=1353&height=1400&name=Cornelia%20Parker_Bullet%20Drawing%20(Crosshairs)-1.jpg)

Bullet Drawing, 2010. Lead bullet drawn into wire, 53.5 x 53.5 x 4.5cm.

Cornelia Parker

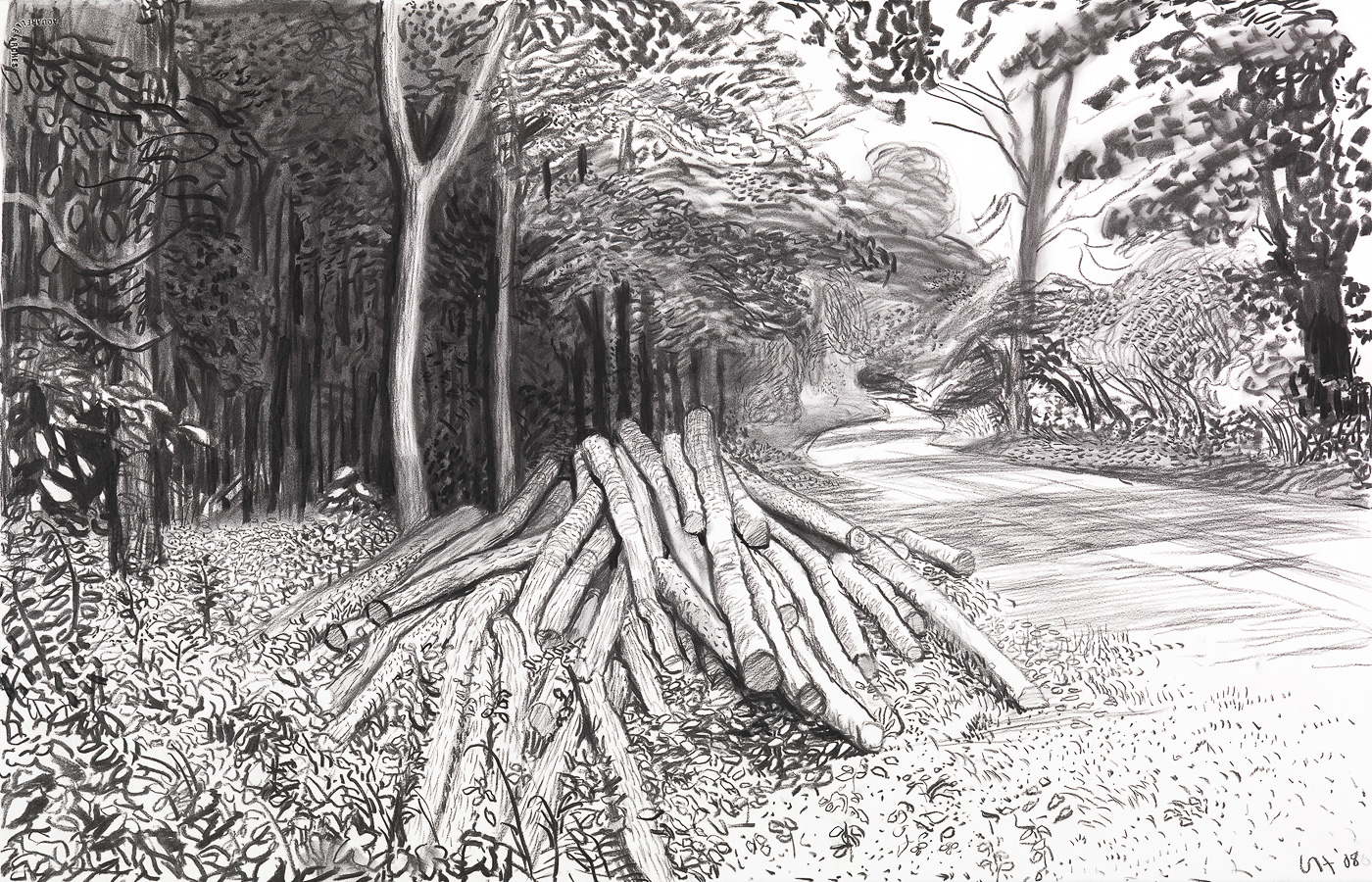

David Hockney

“Drawing makes you see things clearer, and clearer, and clearer still. The image is passing through you in a physiological way, into your brain, into your memory— where it stays—it’s transmitted by your hands... it’s a deep, deep desire to—depict.”

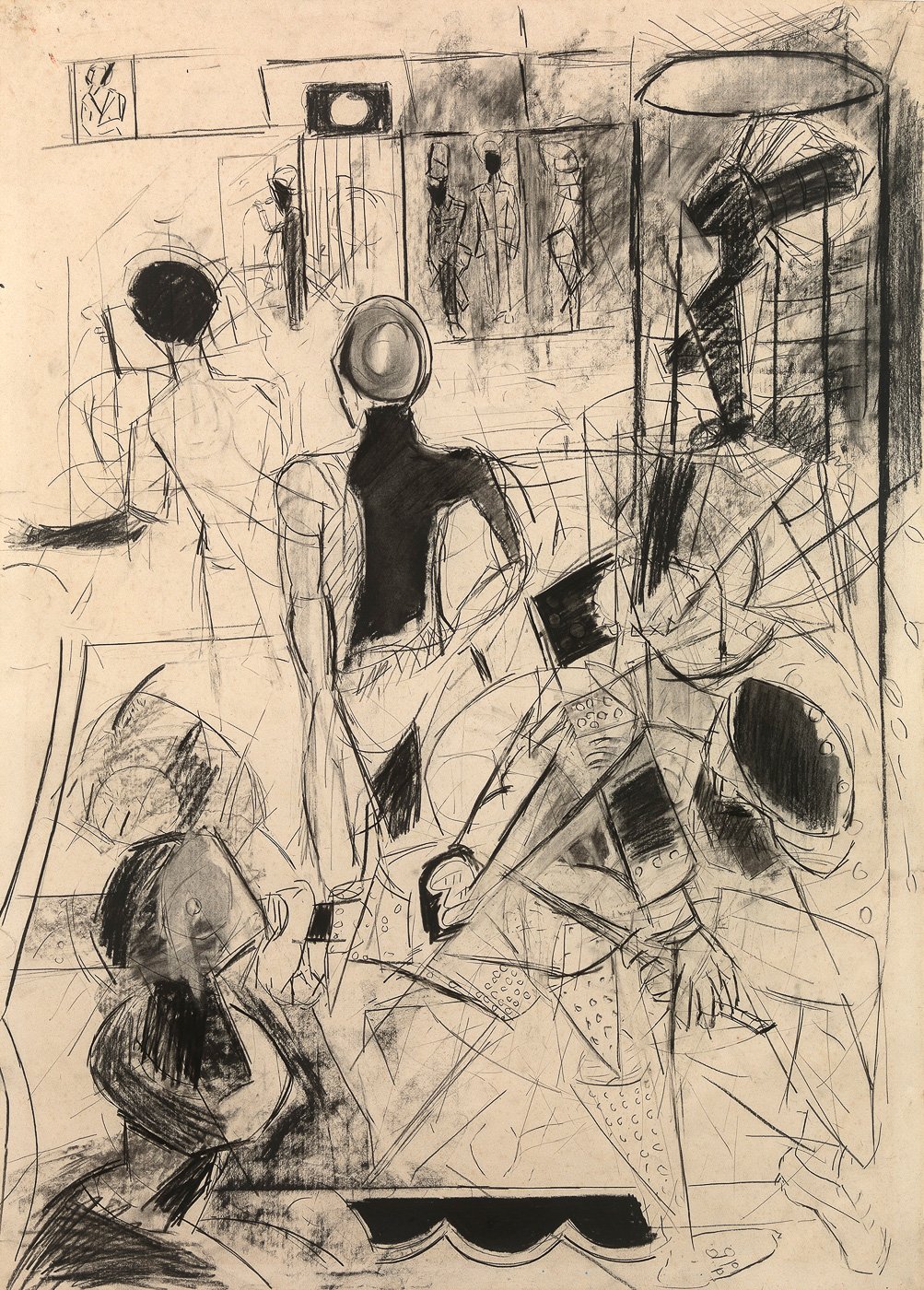

Denzil Forrester

Gesture drawing is “not about what the subject looks like, not even what it is, but drawing what it is doing.”

Eileen Hogan

“I see through drawing. Drawing makes me notice in a different way and find out what I think, what matters to me. It’s a negotiation with the subject, getting to know it. Whether a portrait or a building, the authenticity comes through staring, almost forensically, then filtering which is almost subconscious. Layers of memory, history and emotion overlap with looking. Drawing is like breathing—magic.”

Es Devlin

Redraw the Edges of Yourself, 2022. Mixed media, 60.9 x 15.4 x 85.4cm.

Es Devlin

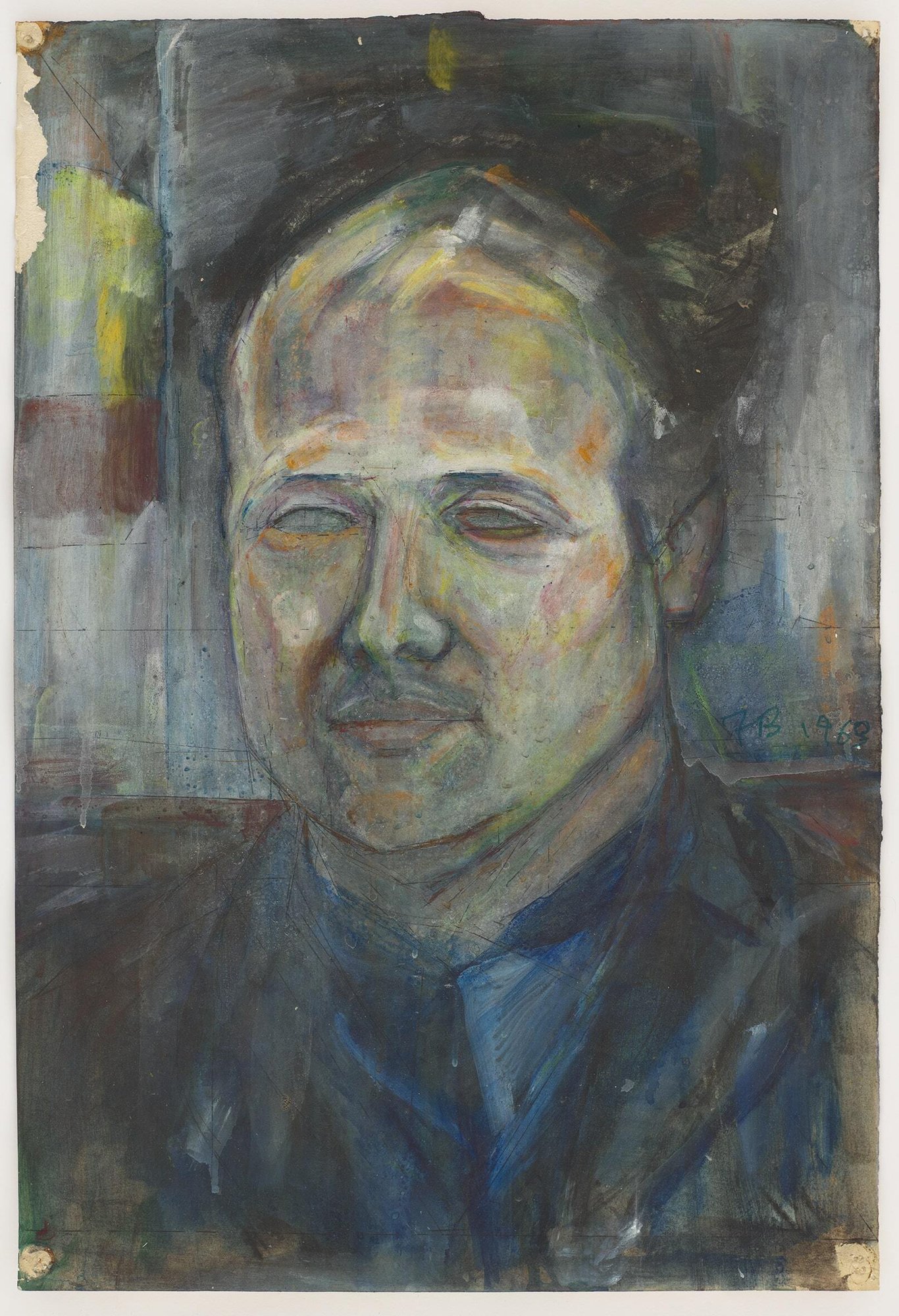

Frank Bowling

“Drawing was very important because the people that I admired, the working artists, the student artists and people working directly from life were very keen on having models and I modelled for them. I suddenly, during this time, got the urge...

I’d been sitting for so many people; I got the urge to do it myself. I felt competitive too with those artists who drew all the time when I wasn’t doing drawing. At the Royal College, the whole training was about life drawing, drawing for life. It came out of that, it came out of me working out for myself how, not having been trained, how to draw, how I could teach myself to draw. Today, I still have the inclination or the remnants of that way of proceeding. I still tend to draw my pictures with the materials themselves. I want the drawn lines to operate separately and by themselves, but they must fit into what they’re in: the flat, plain colour.

I’m aiming all the time to get a perfect rectangle, and thus drawing, just drawing is the plan.”

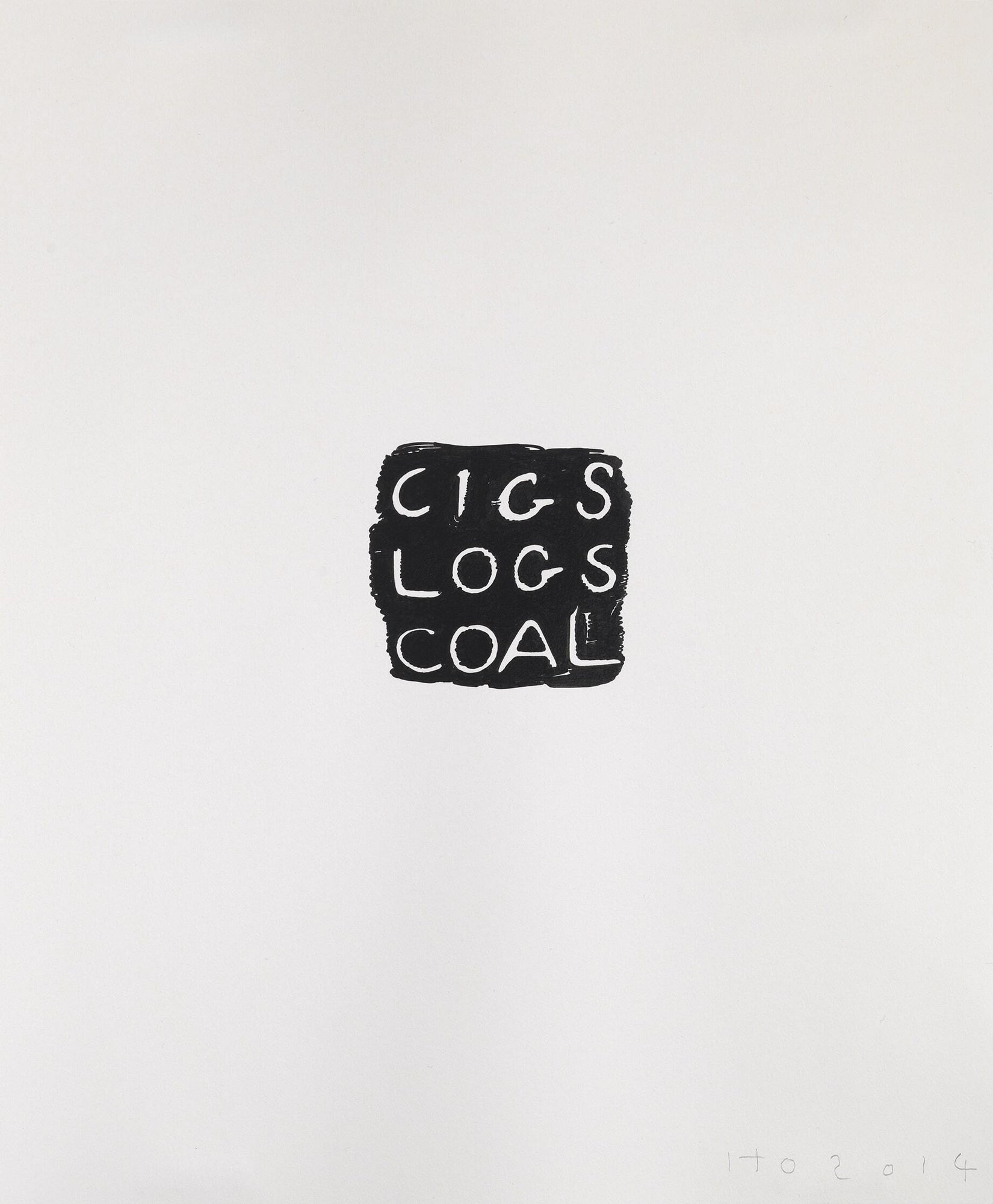

Humphrey Ocean

“Drawing for me is like the very first time I had to try and make the H that my name begins with.”

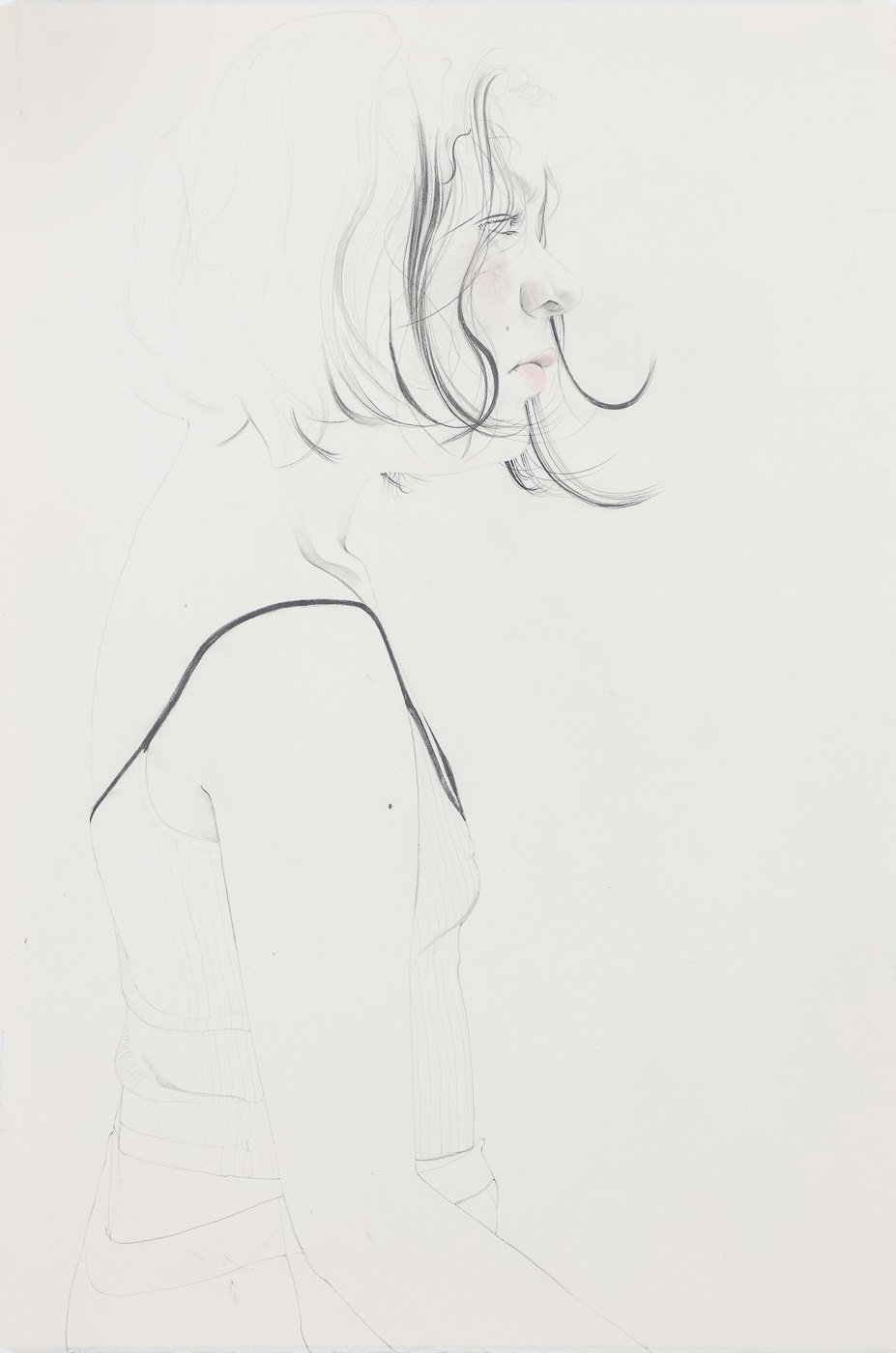

Ishbel Myerscough

“Drawing is a language I feel I can speak and understand, more than words. With a piece of paper and something as simple as a pencil we can chart, discover, explain and inform, we can create a surprising magic: maps, emotions, illusions and history. A universal language that doesn’t need translation.”

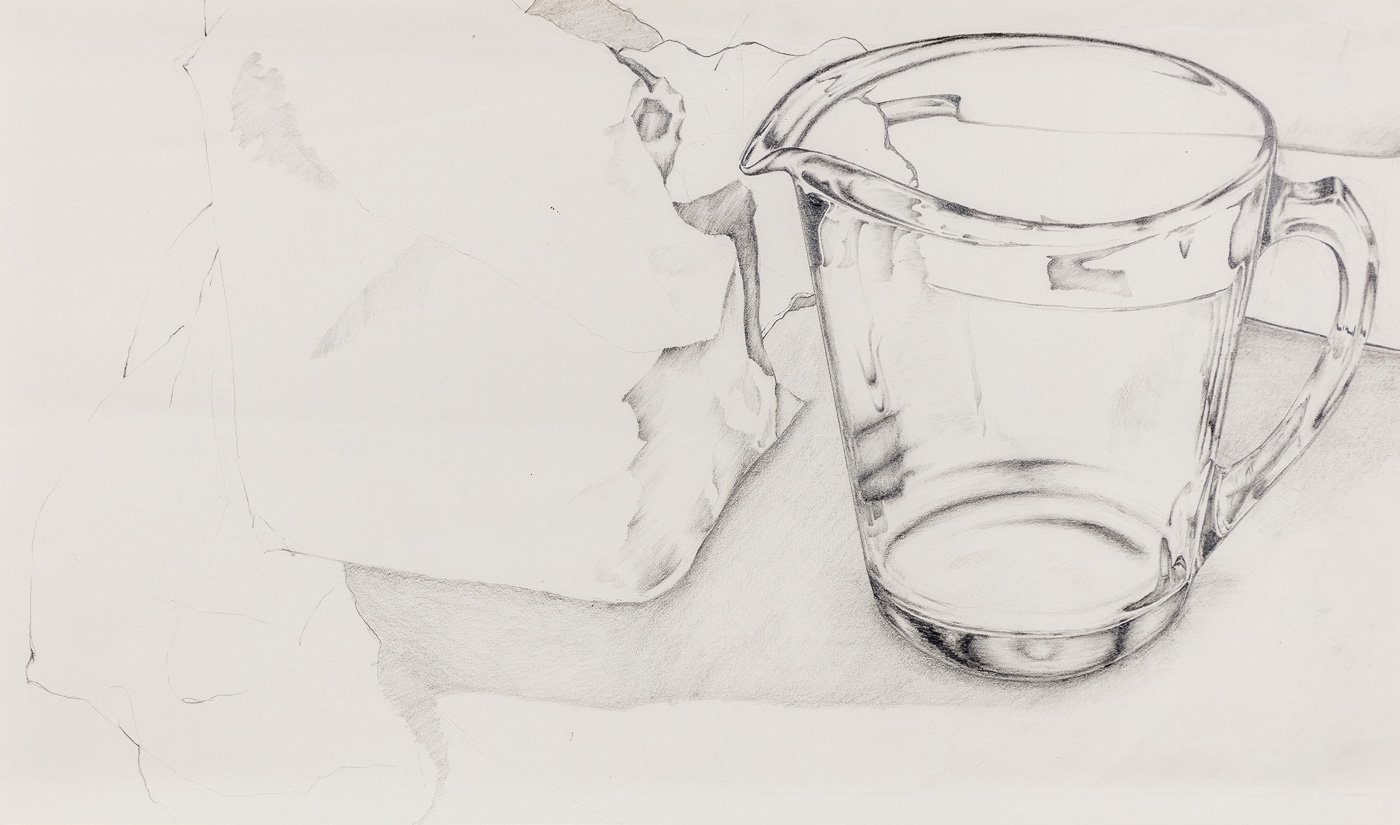

Jony Ive

“As a young boy, learning to draw taught me to see. It gave me the happiest pause to be quiet and truly engage with the physical world. Now my drawings tend to be in service of designing and creating. They are immediate expressions of a thought. They are notes to myself giving body to an idea.”

Observational drawing of Pyrex measuring jug, 1981 (Aged 14). Pencil on paper, 43 x 23.8cm.

Jony Ive

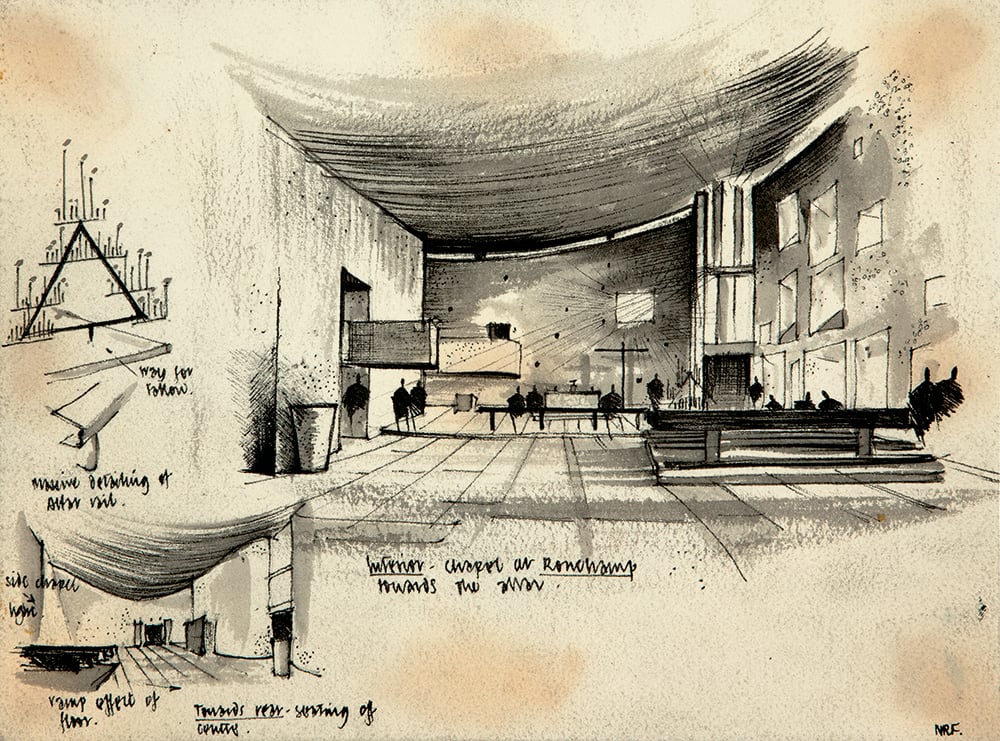

Norman Foster

“I sketch all the time. I see sketching as a means of communication. In some ways it’s a dialogue with oneself—the visual equivalent to the notes or lists that you might jot down. Architecture is as much about the fine print as the headlines—the tactile details, which are literally close enough to touch. Sketching, for me, is a vital way of exploring these concerns. I have never thought of the sketches as precious and, in the past, I was rather reluctant to exhibit them. It felt quite strange if they were seen out of the context of an individual project. Although the computer has revolutionised the way we work, we still draw by hand and model making still plays a central role in the creative process. The pencil and computer are very similar in that they are only as good as the person driving them.”

Quentin Blake

Man and Stork in Conversation, Uplifted Series, 2024.Pen, ink & watercolour wash on Aquarelle Arches fin watercolour paper, 37.5 x 26.5cm.

Quentin Blake

Rachel Jones

“Drawing opens you up to the magical process of connecting to the imaginative realms within yourself via the actions of your hand.”

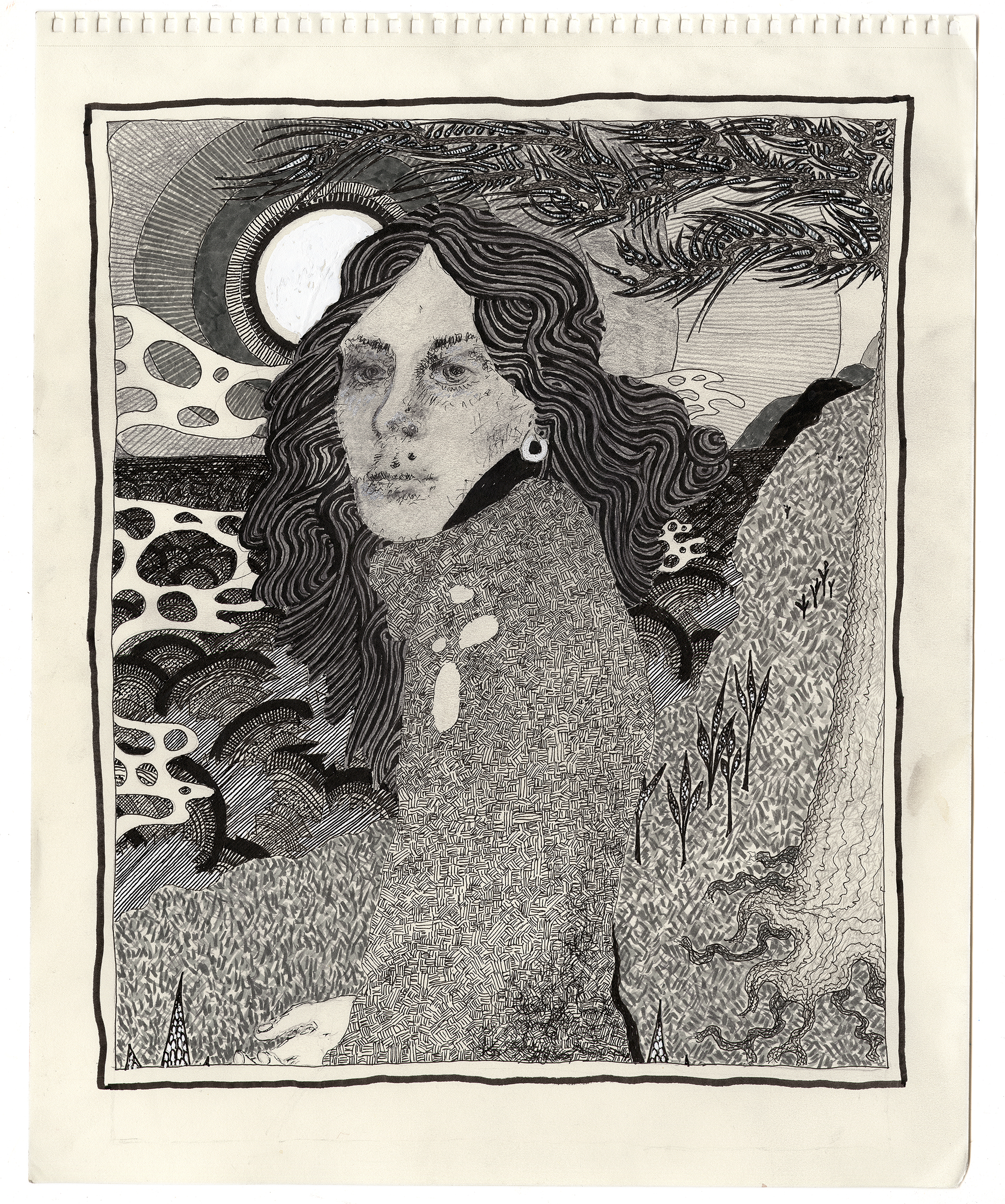

Rufus Wainwright

“I’ve always been drawn to drawing. In my extreme youth it was a tool for discovery and experimentation, then when music took over I put the pencil aside. But during Covid I returned to the silent discipline and instantly realized that in this day and age, a day and age consumed by sensual excesses never before experienced by humanity, drawing has now become for me a means to maintain sanity, a necessary exercise to ward off the dark powers of the vampiric forces of modernity. Basically a cure.”

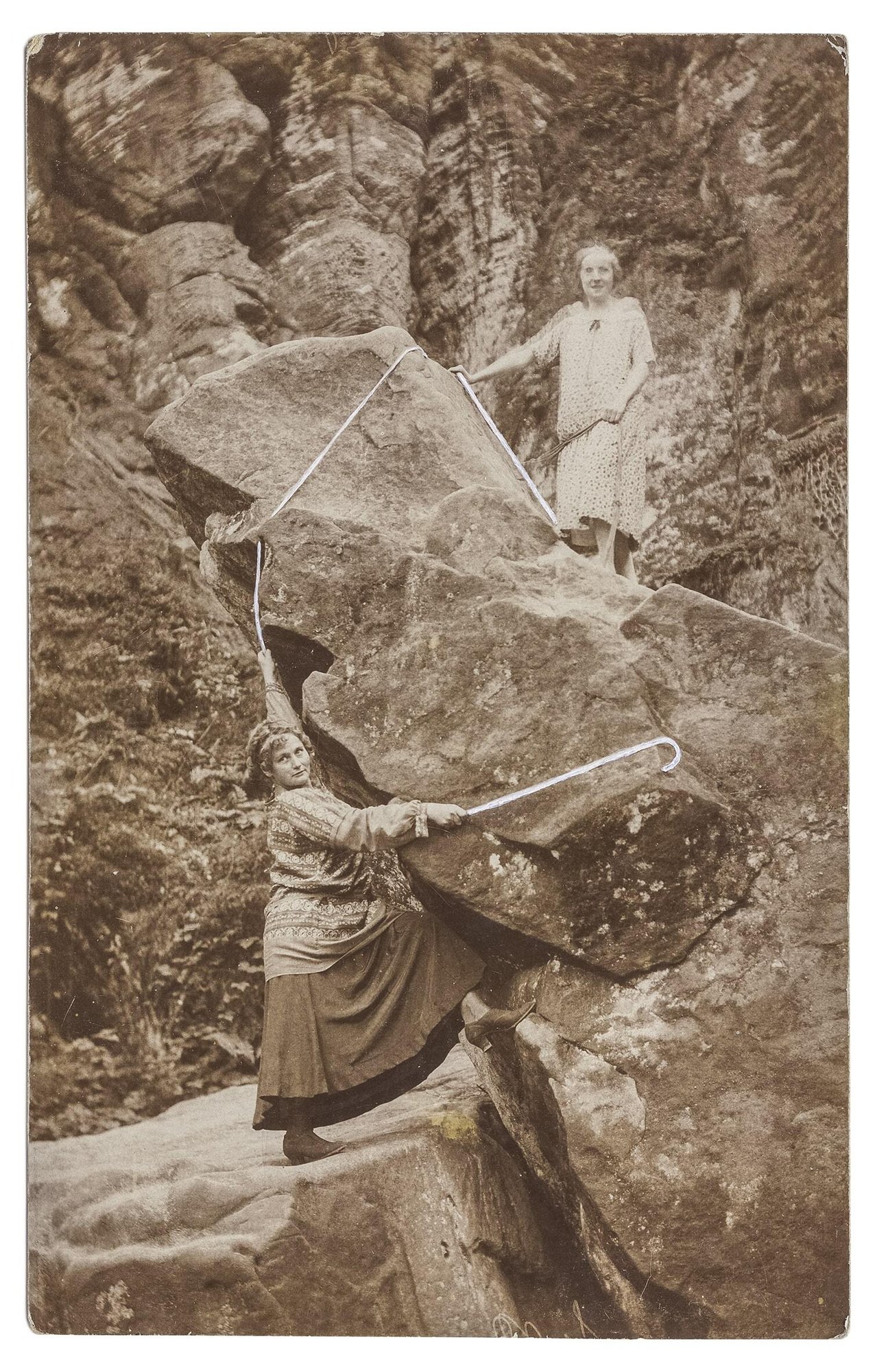

Tacita Dean

“The one surface I draw on seldomly is paper. I am much happier with found surfaces, surfaces with a history. Around the time I made Nefertiti, I was painting small interventions in white gouache on postcards and photographs from my collection. I was also working on a series, which I named ‘petramorphic works’: seeing human or animal form in rocks and stones. The women in this postcard, intentionally or unintentionally, appear to have delineated, or made visible with their rope and walking stick, the perfect head in profile of Nefertiti.”

Thomas Heatherwick

“These drawings were produced in 1991, when I was 21, studying in Manchester, dreaming of how I could construct my first ever building.

At that time, like almost every other student, I was working alone. I didn’t have a studio with amazing collaborators I could discuss things with; share the problems I was encountering, and then work tout how to solve them.

These drawings are my “working it out” thinking, in the same way that someone studying mathematics might share their workings out, to show how they reached a particular answer.

At that time, drawings such as these were also my way to make a small “mini me” version of reality for myself, in the same way that someone might build an architectural model to check how good their idea actually is.

They were a way to get even more excited about the ideas you were having.

Now I work with a group of 250 people and thinking is not a process that has to be done alone. Me and my team work together in different ways on every different project.

And while I do still draw with pens and pencils when I’m alone, there’s now a more significant kind of drawing that happens. It happens in the multitudes of conversations we have, as we grapple together with the issues that architectural projects throw at you.

When I did these drawings 34 years ago I assumed my working life would be lived in relative obscurity. I never dreamed it would turn out to be the beginning of an architectural journey that would lead to shaping public places and spaces all over the world.”

Pavilion Sketch, 1991. Tracing paper, pencil and ink, 42 x 50cm.

Pavilion Sketch, 1991. Tracing paper, pencil and ink, 42 x 50cm.

Thomas Heatherwick

.jpg?width=1395&height=1800&name=Tim%20Burton_Untitled%20(2).jpg)

Tim Burton

“Drawings are like an abstract diary for me… a time, a place, a feeling. Nothing literal, but a memory.”

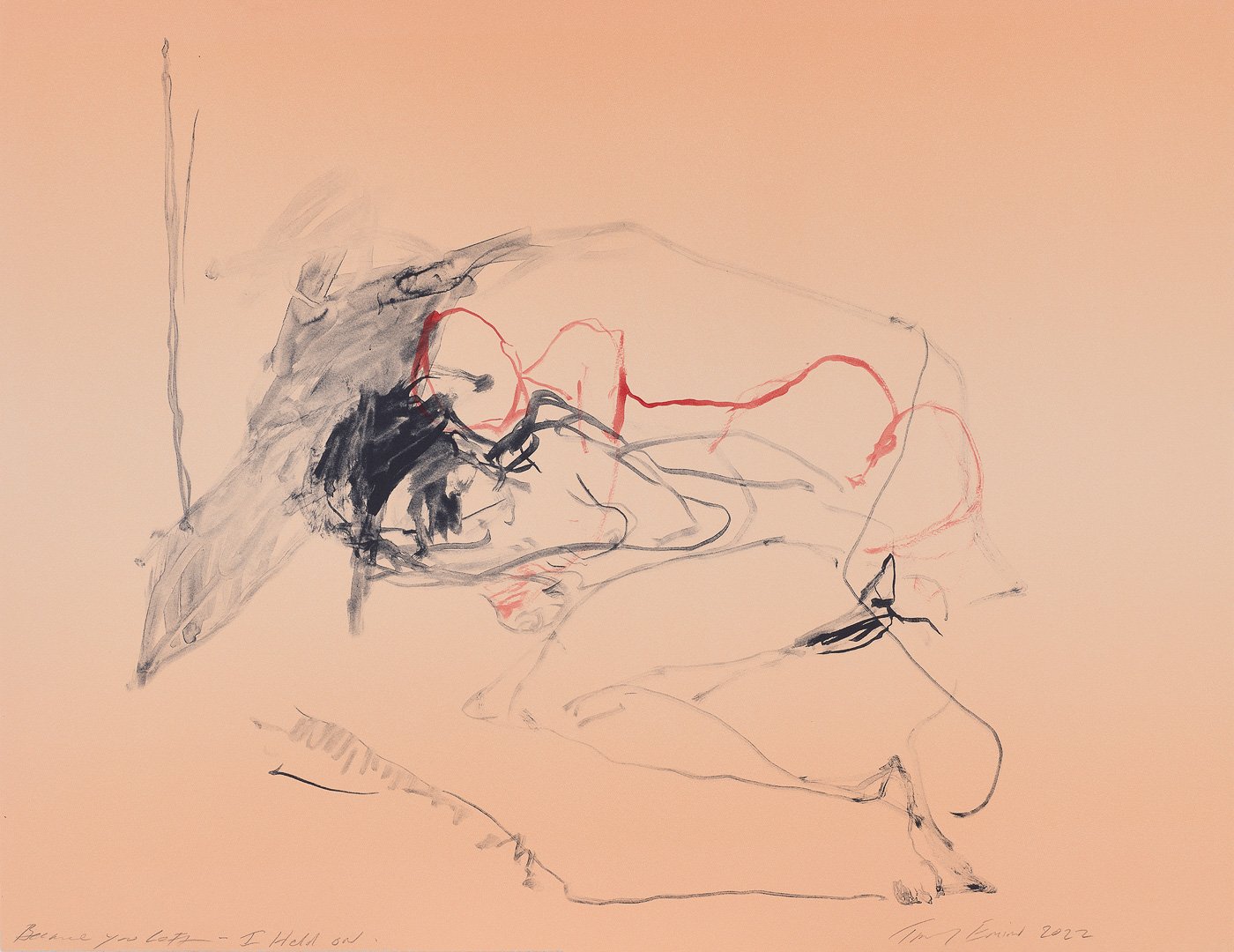

Tracey Emin

Because you Left – I Held on, 2024. Acrylic on lithographic background, Somerset Velvet Warm White Paper 400gsm, 65 x 83.8cm.

Tracey Emin